The Wrong Wright Story 3

Tom Crouch's Wings: A History of Aviation from Kites to the Space Age

a critique by Joe Bullmer

This is the third article in a five-part series presenting critiques of four of the most popular books and the most prominent TV documentary produced concerning the Wright brothers’ development of a manned, powered, controllable airplane. Previous reviews discussed Fred Kelly’s 1943 book The Wright Brothers, A Biography, and Peter Jakab’s 1990 book Visions of a Flying Machine.

This article

discusses Tom Crouch’s book Wings: A History of Aviation from Kites to the Space Age published in 2003 by the Smithsonian, ISBN 0-393-32620-9. This 725-page

book undertakes the monumental task of covering all airplane development from da

Vinci to the 21st century. In this review,

a couple of the book’s comments on 19th century developments are

addressed, along with its description of the Wrights’ work leading to the final

version of their Flyer III aircraft in October of 1905.

These critiques are being done by an aircraft design and performance engineer and author of The WRight Story, The True Story of the Wright Brothers’ Contribution to Early Aviation. That book contradicts much of the content of the books and videos reviewed in this series. The author of these reviews has also published four reviews of technical papers presented in The Wright Flyer-An Engineering Perspective, and two articles concerning the Wrights’ testing at Kitty Hawk, all of which have appeared at this site over the past couple years.

Some explanations appearing in previous articles are repeated in this one. A number of the same mistakes are made in this book, and each of these articles is intended to stand on its own. Forbearance is appreciated. Technically competent comments on these articles, or The WRight Story, are welcomed.

Chapter 1

Page 33: The author, without citing a reference, claims here that Sir George Cayley, in his 1809 article in Nicholson’s Journal of Natural Philisophy, Chemistry, and the Arts, identified an area of low pressure on the upper surface of a cambered wing. Actually, Cayley mentioned “a slight vacuity immediately behind the point of separation ….under the anterior [forward] edge of the surface.” He envisioned this air trapped under a thin cambered wing moving back under the wing and eventually being forced downward by the aft portion of the cambered wing, thus imparting the upward force on the wing.

|

| Sir George Cayley, aviation pioneer |

On the same page, Crouch claims “Cayley had a lifelong preference for oars as propulsion.” Actually, in spite of an early drawing showing oars, Cayley was well aware of the futility of such a scheme. Over most of the second, third, and fourth decades of the 19th century, along with activities unrelated to aviation such as serving in Parliament, Cayley searched for a lightweight mechanical source of rotary power. Unfortunately, by the middle of the 19th century studies of contained explosions of petro-chemicals were just beginning, so Cayley gave up his search for mechanical power and returned to gliders.

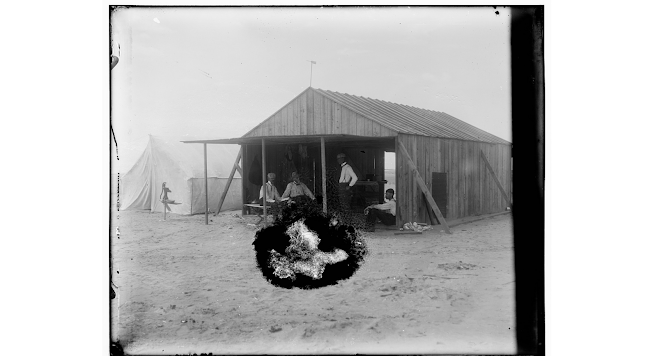

Page 36: Orville Wright is quoted as saying “Henson, Stringfellow, and Marriott made no contributions to the art or science of aviation worth mentioning.” But then Orville went on, “Every feature of Henson’s machine had been used or proposed previously. His mere assemblage of old elements certainly did not constitute invention.” I find it curious these statements were included in this otherwise complimentary book. Except for their chain drive of propellers and interconnected rudder and warping, which soon had to be abandoned, Orville’s statement applies exactly to what he and his brother did. In this one statement Orville’s judgement actually disqualifies himself and his brother as inventors.

|

| William Henson and his Aerial Steam Carriage |

Page 43: Here Hiram Maxim’s huge 1893 flying machine is described as having a 180 hp steam engine driving one 18-foot propeller. In fact, numerous photos show that it had two such engines driving two 18-foot propellers. This is important since the engines were to be independently throttled to yaw the vehicle which, in conjunction with dihedral on the outer wings, was intended to enable turning. The vehicle was never flown freely and this scheme was never validated. It also was the only prominent vehicle prior to the Wrights to feature an adjustable horizontal forward surface or canard (which was also never used).

Chapter 2

Page 65: The author credits the Wrights with the “genius” that was “never more apparent” than in devising their wind tunnel balance that, through a mysterious “cascading chain of forces”, could indicate the relative magnitudes of the lift and drag forces on a miniature test section of a wing. In fact, the device, indicating lift versus drag, was simply a flexible parallelogram that was explained to them by Dr. George Spratt during his visit to their Kitty Hawk test site during the summer of 1901. Wilbur admitted this in an October 16th, 1909 letter to Dr. Spratt, and Orville admitted it in his sworn deposition for the 1920 Montgomery case.

|

| George Spratt's visit to Kitty Hawk, 1901 |

Wind blowing on the test wing would allow it to pull the parallelogram to an angle, the trigonometric tangent of which would yield the wing’s lift-to-drag ratio. The Wrights modified this design to show the force on a test item versus the drag on flat plates perpendicular to the air flow. It appears the whole idea of a wind tunnel was raised by Octave Chanute, Dr. Spratt, and Mr. Huffaker at Kitty Hawk during their visit in 1901. There is no record of Orville or Wilbur even mentioning one before discussing it with Chanute and his cohorts that summer. Chanute also showed them detailed photos of wind tunnel components during that visit.

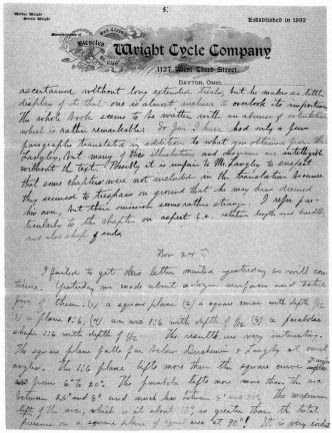

On this same page the author claims the Wrights “discovered” the proper wing camber and aspect ratio with their wind tunnel. What they discovered was that they had to abandon the totally inappropriate wing shapes they had been using for two years in an attempt to suppress the instability caused by their canard. Instead, to get sufficient lift they had to revert to the wing shapes that had been used previously by Lilienthal and many others. They also admitted this in a November 24th, 1901 letter to Octave Chanute.

|

| The Wrights' letter to Octave Chanute |

Page 66: Here it is claimed that the original 1902 glider “sport[ed] a rudder”. In fact, it did not. What it had were two fixed vertical stabilizers. Only later, when it was found that this made the spin problems worse, was it changed to one moveable vertical rudder. (A fixed aft surface is a stabilizer. A moveable one is either a rudder or elevator.) Deflection of that rudder kept the glider from spinning in when warping was used to correct an inadvertent roll. (See The WRight Story, Chapter IV, or the discussion in the previous article concerning page 112 of the book “Visions of a Flying Machine” for more detail.)

|

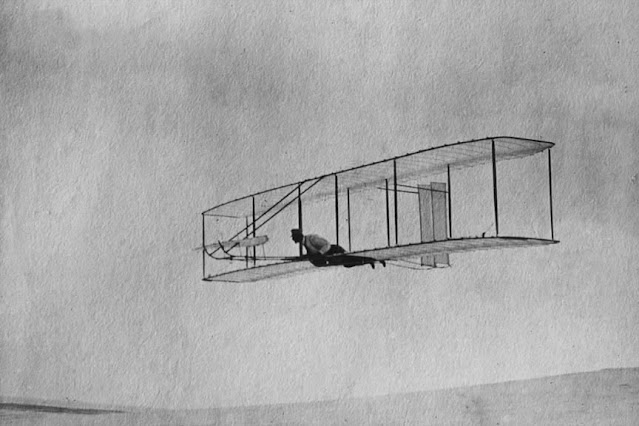

| The 1902 Wright glider. |

Page 67: It is claimed that the Wrights’ first engine developed 12 hp “after it had been running for a few minutes.” Actually, with only convective water cooling and a poor oiling system, the first engine would overheat within little more than two minutes of running.

Page 70: The ludicrous statement attributed to Orville Wright by the Dayton Journal in 1923 is presented, claiming that the 1903 “Flyer” could have flown for 20 minutes at 1,000 feet of altitude. Not only would the engine have overheated and seized in little more than a couple minutes, but the vehicle only had enough power to climb about half way out of ground effect, i.e., only about 15 feet above the ground. And this vehicle could not be effectively controlled! It’s disturbing that the National Air and Space Museum’s Curator for Aeronautics would write a book without being aware of any of this.

Page 81: The device that allowed the Wrights to accomplish a successful test program at Huffman Prairie in 1904 and 1905, their catapult, is mentioned, again without any credit whatsoever being given to Octave Chanute for introducing the concept and basic design to the Wrights. This suppression, or ignorance, of Chanute’s contributions to the Wright’s efforts (as listed in the discussion in the previous article in this series regarding page 84 of the Jakab book) is universal with Wright authors, as is lack of recognition of Chanute’s and Spratt’s contributions to their wind tunnel. These, and other such omissions, are used to build the myth of the Wrights’ legendary “genius” enabling them to see the solution to every problem they encountered completely on their own.

Further along on page 81, disconnecting the rudder from the warping control to enable maneuvers is mentioned. Their 1903 aircraft couldn’t lift itself off of the ground on its own, couldn’t climb even half way out of ground effect, damaged itself in half of its landings, was totally unstable, couldn’t be controlled or turned, and had an engine that couldn’t run more than two minutes. But by October of 1905 they had developed an airplane that could be catapulted into the air with no headwind, could climb out of ground effect with an engine that could run over a half hour until fuel depletion, was much less unstable and could be kept under control, could be turned at will, and could be landed without damage. In this book this is all attributed to “growing experience in the air”. Nothing is mentioned of having had to lengthen and strengthen the airframe, completely change the balance of the machine, changing wing anhedral to dihedral, changing size, location, loading, and pivoting of the canard, devising aerodynamic turning aids, also creating cooling, an oiling system, and the fuel feed and mixing systems of the engine, and going through numerous propeller designs. To say nothing of numerous crashes, busting up airframes, wings, propellers, even engines, along with a few minor injuries to themselves.

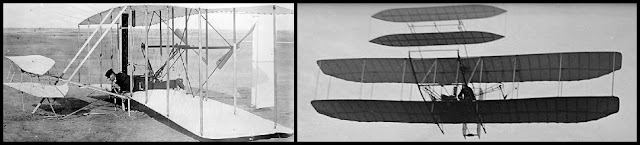

|

| Left: Wilbur with the 1903 Wright Flyer; Right: the 1905 Wright Flyer III |

I understand a book that purports to cover the entire evolution of flight up to the present day must take occasional shortcuts. But two years of testing, modification, and results were just summarized here in one paragraph.

Page 124: The erroneous and demeaning assertion is made that the Wrights “were far less interested in scientific theory or the fundamental physical principals underlying flight”. The author of Visions made the same assertion in person, putting it more strongly by saying that “They were engineers, not scientists”. Obviously, these history majors don’t appreciate what it takes to do competent professional aircraft design engineering.

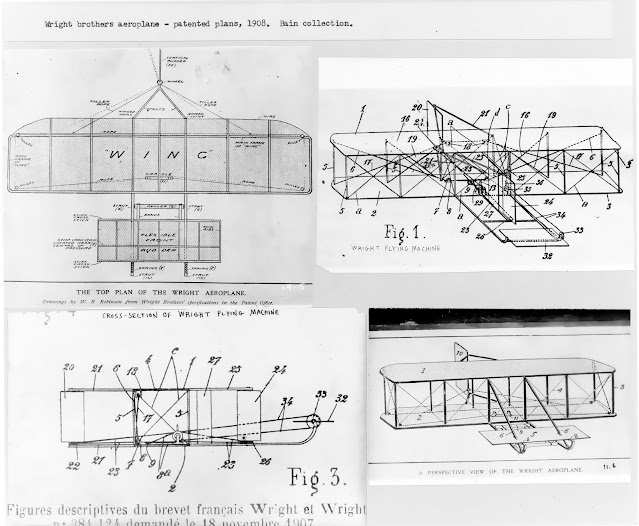

The Wrights thought they understood the physical principles involved. That is what distinguished them from most of their predecessors. Unfortunately, in some cases they were wrong, including the physics principal most basic to their airplane: how a cambered wing generates lift. This is verified by a number of their writings, including their major patent, giving erroneous explanations of lift. And they paid dearly for that mistake, largely wasting their first two years of development work and testing, and adopting a configuration that soon put them behind their competition.

|

| The Wright's 1908 patent designs |

In the next two paragraphs the author goes even further into unfamiliar territory, claiming that engineers don’t agree on how a horizontal spinning cylinder generates lift. He then goes on to settle this dispute for them by giving an explanation without mentioning boundary layers or stagnation points, key elements to understanding the phenomenon. Perhaps the “engineers” advising him should go back to their first semester aerodynamic texts - if indeed any of them ever did study aerodynamics.

Pages 134 & 135: The expenditures by various countries on aviation up to WWI are listed showing the United States ranked fourteenth behind such countries as Chile and Bulgaria. But no mention is made of this largely being due to the Wrights stifling the development of aviation in the U.S. with their various patent suits and legal actions. Much of this was enabled by judgements from the notoriously inept and corrupt New York District Judge John R. Hazel. They were demanding 10 percent royalties from any airplane related incomes, including exhibitions, and 20 percent from their only real competitor, the Curtiss company. Not only did the Wrights suppress aircraft production and development in the U.S., but even basic aviation research in academia was largely eliminated because of the resulting lack of industry interest or funding for such research.

|

| Judge John R. Hazel |

How ironic that the very guys that, up through 1908, had put the U.S. first in the world in aircraft development, managed in the next five years to drag the U.S. down to a handful of uncompetitive unserviceable military airplanes while the major European nations each had hundreds of modern capable combat aircraft. In fact, the original Wright Company only lasted five years, and the second, the Dayton Wright Company, only survived WWI by building a faulty British design under license.

Page 147: For some unstated reason the Wrights’ commercial failure is primarily attributed by this author to their pusher propeller designs having the propellers located behind the wings. This is odd since the success of everything from the Republic Seabee to the Convair B-36, the U.S.’s first true intercontinental bomber, would indicate otherwise. Hundreds of B-36’s were produced, constituting, along with B-47’s, the U.S. strategic nuclear deterrent from the late 1940’s through the 1950’s. Obviously its six huge pusher propellers were no impediment to its success.

|

| Republic Seavee and Convair B-36 |

No mention is made of early Wright aircraft’s lack of wheels complicating ground handling and requiring a rail and large catapult for launching, canard induced stability problems, warp-induced spins, no useful load capability, and a disproportionate share of crashes and crew deaths. These deficiencies rendered Wright airplanes essentially useless for the military, the first large American user of aircraft. By the time the Wrights eliminated these problems the rest of the aircraft industry had left them far behind.

Summary

Wings was an ambitious undertaking, attempting to cover over two centuries of aircraft development and production in 725 pages. Over 100 contributors are listed in the Acknowledgments. However, again, as with Visions, the last book reviewed, only very few of these contributors were ostensibly qualified to contribute any technical assistance, and these people apparently had woefully inadequate knowledge of the Wrights.

As would be expected in a Smithsonian book of this scope, many hundreds of notes were listed at the back. However, only one of the comments made in this summary pertains to a passage in Wings supported by any of these references, that to an article in the Dayton Journal in 1923 quoting a universally discredited statement by Orville Wright.

It appears this author relied heavily upon the advice of the author of Visions of a Flying Machine since a number of the same exaggerations and errors appear in both books. Also familiar is the technique of replacing research with assumptions and opinions. One would expect more on such an important subject from the highest level of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

Any book of this scope would, of necessity, omit much detail. But that does not excuse the inclusion of incorrect information, particularly on what is universally considered the origin of the entire technology and industry. This is particularly unfortunate since so many “aviation historians” have relied on this material as the basis for their work.