Were you the photographer in this picture — precariously perched on an assistant’s shoulders, standing on sand, in a blustery wind, varying 24 to 27 MPH? Had it been you, simultaneously snapping one of the most significant events of the 20th Century while performing this balancing act, could you then have forgotten the event?

Bizarrely, that’s one of the less curious aspects surrounding the iconic “First Flight” picture of the Wright Brothers which is examined below.

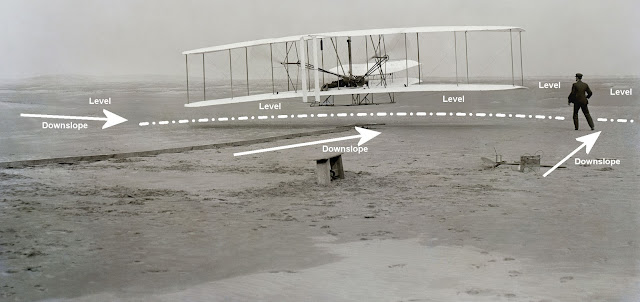

Despite an astounding conclusion, we are unable to offer much in the

way of new facts while getting there: It’s all in the picture, and has

been so since the image entered the public domain on September 1, 1908.

It just needs looking at with a clear, critical, open mind, plus a basic

knowledge of perspective.

Kitty Hawk — A New Perspective

The Earth is flat and light travels in straight lines. On the

Global and Cosmic scales, both these statements are incorrect, but for

the purposes of everyday life they are not only good enough, but they

also help us make sense of the world. Especially the painter; and

particularly, the landscape artist.

Here,

we shed new light on the “perspective” of the Wright Brothers’ reported

flights at Kill Devil Hills, Kitty Hawk, in December 1903. The validity

of the assertion that those short flights constituted the first by an

airplane rests on the claim that they took-off from level ground;

traversed level ground; and landed on ground which was at the same level

as that from which the take-off had been made. Level ground; the

Brothers and their supporters have been keen to stress that there was no

downhill gliding to assist, and thereby invalidate, the powered flights

of December 17.

For example: Orville Wright in How We Invented the Airplane:

“These flights started from a point about 100 feet to the west of our

camp. The ground was perfectly level for a mile or two in every

direction, excepting those towards the big and the smaller Kill Devil

Hills. The ground was level in the directions towards those hills for a

distance of a quarter of a mile.”

And

again, in the supposed telegram to their father: “Started from Level

with engine power alone.” This reiterated by Orville in a letter to Max Herzberg, as late as July 11, 1942: “All these [on December 17] were made from level ground….”

Or

American National Biography Online, “four powered flights made from a

strip of level sand.” Or, indeed, just about any other biography of the

Wright Brothers.

Had

those flights taken off downhill, Wilbur and Orville Wright would be

branded frauds and liars. “Level ground” is, literally, the foundation

of the Wright Brothers’ claim to have invented the airplane.

Generations

of aviation historians have looked at the iconic “First Flight”

photograph and found nothing amiss. After all, the image is instantly

recognized around the world, and even appears on US pilot’s licenses –

surely, the hallmark of its authenticity. The Wrights’ reputation lives

on, untarnished. But has anyone asked the opinion of an artist?

It is hoped that the reader will not mind sitting through a

short lesson in artistic perspective. Study material is no more complex

than an illustration from a children’s encyclopaedia of the 1950s.

The “laws” of perspective are governed by Nature and apply wherever the

eye of the observer might happen to be. Imagine the viewpoint of the

trolley wire maintenance man on his raised inspection platform. If his

head is between the two wires (don’t try this at home!) those wires will

seem to be short and horizontal, originating beside each ear and

terminating in front of the nose. The roof of the trolley-car will be

visible in this elevated view, and, in compensation, the road will seem

to rise more steeply to meet its pre-ordained vanishing point. The

maintenance man will see more road than his ground-level assistant,

because he is looking down from higher level.

North

Carolina being part of the Universe, the same rules apply at Kitty

Hawk. This is demonstrated by Wright-related pictures kindly made

available by the US National Park Service (NPS). The

Wright Brothers National Memorial includes a full-scale,

three-dimensional diorama of the First Flight; and a paved pathway to

show the claimed 852-foot flight of December 17, 1903, marked with

placarded monoliths to show the shorter sorties of earlier that day.

Nor

are forgotten in the diorama the Life Savers who assisted with

maneuvering the Wright Flyer on the ground, and who were named by the

Wrights as witnesses able to verify their claim that great events took

place that day. Specially depicted is John Daniels:

Orville Wright later (unaccountably, only some two decades later) made it known that it was Daniels who took the world-famous First Flight picture. When interviewed for a magazine article, following his naming, Daniels “could not remember” having operated shutter on the Wrights’ Korona V plate-camera, but also recalled that his job had been to hold the wingtip, on, presumably, the opposite side to the camera. That curious episode has been debated previously on this blog and, anyway, for present purposes, it matters not who squeezed the bulb to take the picture. Suffice it to say that Daniels is immortalized standing beside a standard 4-foot camera tripod, which means that the lens of the apparatus that took the renowned photograph was about 4 feet 3 inches above ground level.

An

appealing picture taken at a recent commemorative event by the NPS

photographer shows a child standing about half-way along the replica of

the 60-foot launch rail used by the Flyer. For compositional reasons,

the picture is taken at slightly below the height at which Daniels’

tripod picture would have been taken. Even so, this (about 3½ feet,

maximum) is slightly greater in height than the child (3 feet, or

under), so her head appears to be below the horizon.

More of interest, is an enlargement of the figures in the middle distance.

The

horizon — that is the edge of the flat plain of land, ignoring any

trees or hills in the distance — is level with the navel of the nearest

man (in a black jacket) on the path. In other words: lens height (3½

feet). The man to the right, is only 40% of the apparent height of the

first man because he is farther away, but the horizon is level with his

navel, too.

Back

on the path, a third man, farther away still, is only 20% the height of

the first gentleman and, yes, the horizon and his navel are level. A

couple of figures can be discerned even more distant; again the horizon

is in the same place on their, yet smaller, bodies.

It

seems to be a rule of perspective that anything the same height as the

camera appears to be level with the horizon when all is on a flat

surface. To double-check that, the NPS offers another picture of the

Wright Brothers’ “Runway” from an interesting perspective.

To record the scene, the photographer is standing behind the crowd, with the camera held high above their head (about 7 feet above ground level). From this elevated vantage point (recall the trolley wire maintenance man), everybody’s head is below the distant horizon.

That goes for the same, tall man in that black jacket. He needs to stand on a foot-high box if his cap is to touch the horizon — making his new “height” 7 feet: the same as the held-aloft camera. To reiterate: Anything at camera lens height looks level with the horizon.

Inventing an airplane: simple! Bending light is the clever bit.

Let’s now check this new-found knowledge against the original

photograph of the Wright Brothers’ “runway." The shifting sands have

moved the Kill Devil Hills some 450 feet since 1903, so they are not at

precisely the same co-ordinates, but around them is still flat ground,

and that’s all that matters.

The best-quality version of the iconic First Flight picture

can be downloaded from the Library of Congress website. For

authenticity, image 00626 is preferred because, even though it has a

corner of the glass plate missing, it shows the near-end of the launch

rail, and the sand-anchor for restraining the "Flier" before launch.

Other

versions of this picture one normally sees have been photo-shopped by

way of repair but, although this has not been undertaken with any

ulterior motive, the original, yet damaged, copy serves its purpose

adequately. However, that high quality version is necessary reference

for some of the analysis which follows. The reader is enjoined to

download it, because it includes some very interesting things on the far

left which are trimmed off most printed reproductions of this picture.

One

of the world’s best-known images (above) needs no further introduction.

Therefore, attention can be directed immediately to Wilbur Wright (below), as this enlargement shows.

Wilbur Wright was 5 feet 10 inches tall (for example, the US Federal Aviation Agency teachers’ guide

www.faa.gov/education/educators/curriculum/k12/media/K12_Wright_Brothers_Curriculum_Guide.pdf page 21: “Wilbur

Wright was 5 feet and 10 inches tall and weighed 140 pounds. Orville

Wright was shorter by an inch and a half and was 5 pounds heavier”).

John Daniels’ camera lens was 4 feet 3 inches above ground level.

Discounting

the distant hills, the horizon of the “Level in all directions” plain

reportedly surrounding the launch site intersects Wilbur’s body at his

upper lip, which is 5 feet 5 inches above the ground, and not at his

solar plexus (the 4 feet 3 inches camera lens height) where the law of

perspective says it should. The alignment depicted is impossible if all is on level ground.

Setting aside any notion of darkroom manipulation, two possible explanations present themselves. Pick one.

1.

Wilbur’s impressively large and hyper-active brain is distorting the

space-time continuum around his body, making it appear to be where it is

not.

2.

Wilbur is standing on ground that is at least 1 foot 2 inches below the

ground on which the camera tripod is resting. That is to say: The launch rail is pointing downhill and the hill continues downwards some way beyond the far end of the rail.

Readers

choosing "2" may consider the drop of little significance, but this is a

minimum figure. The movement of the apparent horizon is difficult to

calculate without knowing accurately how far up the slope the rail is

positioned, so 1¼ feet is the smallest figure that is absolutely

provable. Thus, the actual rate of drop is likely to be 2 to 2½ degrees.

That’s not steep in driving or walking terms, but it should be

commented that, in aviation, 3 degrees is the standard descent path for

landing.

Interestingly,

the National Park Service life-size diorama at Kitty Hawk attempts to

overcome the tricky problem of perspective by depicting Wilbur in a

semi-crouching position and raising the whole scene slightly above the

general level of the memorial park, so the horizon is “wrong.” That is

of no account, because reference to the old picture of Wilbur and the

Flyer demonstrates that the apparent size of his body exactly fits

between the upper and lower wings, which gap is 6 feet 2 inches. So, he

is a few feet behind the aircraft and standing at his full height.

I don’t believe in physics. Please provide more proof.

Despite the clear and compelling evidence for a downward launch angle,

it must be conceded that there are many who prefer to believe the

unsupported statements of the Wrights, even when they are in conflict

with the laws of physics, with witness statements, and what they see

with their own eyes. In that case, corroborating evidence might be

helpful to dispel lingering doubts. And it is not difficult to find.

A.

John Daniels (the “photographer” and airplane ground-handler), letter

to a friend June 30, 1933 [spelling errors as per the original]:

“it was on Dec the 17, — 1903 about 10 o’clock. They carried the machine up on the Hill

and Put her on the track, and started the engine, and they through a

coin to see who should take the first go, so it fell on Mr. Orval, and

he went about 100 feet or more, and then Mr. Wilbur taken the machine up on the Hill and Put her on the track and he went off across the Beach about a half a mile or more before he came Down.”

B. John Daniels, 1927 interview with W.O. Saunders for Collier’s Weekly, quoted in The Published Writings of Wilbur and Orville Wright: [regarding second flight]

“We got it back up on the hill again and this time Wilbur got in.”

C. Adam Etheridge, Daniels’ colleague, interviewed simultaneously, added, “I saw the same as Daniels”.

D. The left side of the First Flight photograph shows a land feature indicative of downward-sloping ground. This is on that section of the photograph which is cut off most printed versions of the picture.

The

launch rail is in the foreground and a descending ridge is marked with

three arrows. The camera lens is higher than the ridge (because the

ridge is below the horizon line); the ridge is some 100 feet away and,

therefore a substantial feature, rather than a quirky scrape in the

ground at the photographer’s feet; and that ridge leads down to even

lower, flatter ground.

E. The right side of the photograph shows an abrupt change of surface shade/value, (indicated by an arrow).

The

Kitty Hawk Park land has been stabilized with planted vegetation since

1928, but its original condition is reflected a couple of miles south,

at Nags Head. There, it can be seen that vegetation (darker shade) can

gain a foothold on the level ground, but the constantly shifting sand of

the dunes is a lighter shade. In other words, a lighter color often

indicates higher ground — and it is on that lighter ground that Wilbur

is standing. That said, there are slight variations in sand color

according to light/shade and the moisture it contains, so only the more

distant color variations should be considered indicative of vegetation.

Sand Dune at Nag’s Head

The higher you are, the more you see.

This

combination picture of ancient and modern shows, on the left, Wilbur at

the end of the launch rail, pictured from a camera just past the rail’s

back end. A distance between the two of some 65-70 feet. On the right

is a modern visitor to the memorial park, standing some 20 feet farther

from the rail’s far end, but with the camera about the same distance

along that rail. So, again, about 60-65 feet between the two.

The

images have been adjusted to make both figures the same height. As

noted already, the background landscape extends from Wilbur’s feet to

the level of his upper lip. However, the horizon comes only to the waist

of the modern, black-jacketed gentleman.

Why is there half-as-much-again landscape behind Wilbur? Simple: In that photograph, we are looking down on the landscape from a greater height than the “sub-tripod” vantage point of the color picture.

And

in this comparison, the changes in camera lens technology over a

century are of no consequence. Wide angle or telephoto, it is the

elevation above ground level which is the determiner of how much is

seen, not the quality or magnification of the lens. On

the African plain, the man may view more of the land than the

slithering snake; but the giraffe sees more than the man. It is all down

to (up to?) elevation.

Where on Earth...?

The

next, logical question concerns the location of this raised ground. One

site offers itself with all the effusion of a young “teacher’s pet”

with heart thumping and arm raised high. Three days earlier (December

14), the Flyer had been taken to the greater Kill Devil Hill, where

Wilbur made an attempt at flight which ended in slight damage after 105

feet because of (as the telegram home reported) a “Miss judgement.”

Orville’s

diary records, “We took machine 150 ft uphill and laid track on 8º 50´

slope.” In other words, as deduced from simple geometry, the launch was

made from an elevation of 25 feet above the level ground which

surrounded the hill. That’s a generous helping of free height to assist

an airplane take-off and flight, but it seemed not to concern the

Wrights at that point in their experiments.

The assisting Life Savers, their children and a dog posed for a couple of group photographs just before the flight attempt was made on the 14th. It is scarcely necessary to draw attention to the slope of the hill, or to ask whether, from their 25-foot vantage point, the assembled party was enjoying the same, enhanced view of the land as was allegedly captured by the camera, standing where they were, three days later.

Why

was not the downward view of December 17 as obvious as the uphill one

of December 14th? In part, the answer lies in the fact that one stretch

of black-and-white ground looks pretty much the same as another, unless

looked at critically and most discerningly. Told it is flat, most people

will take that as fact, without checking.

And

cameras can be persuaded to play other tricks, too. Take this photo of

the 1905 Flyer at Kitty Hawk in May 1908, after it had been modified to

carry a passenger.

However, a miracle cure is effected when Orville’s diary entry is recollected. Give the horizon a 8º 50´ slope and not only is all in better proportion and posture, it can also be seen that even in 1908, a hill start (or a falling weight) was needed to get a Wright airplane off the ground under normal circumstances. By accident, or design, the photograph, as originally composed, does not make this clear.

If you can’t persuade the camera to lie....

This blog has previously published its findings on three other

pictures also taken by the Wrights in December 1903. All were found to

be tainted by anomalies which strongly imply that they do not show what

they claim: Wilbur’s “misjudgement” photo of December 14 is a

crudely-faked re-enactment that fails to convince; the “sidle” incident

on the third flight of December 17, contradicts the same-day entry in

Orville’s diary; and the puzzling “852-foot” fourth-flight picture shows

less than 300 feet from the launch rail, as well as what appears to be

an entirely different airplane. Now, we add a fourth Wright picture to

this catalog of dubiousness.

The First Flight picture has been questioned before, but over details which can be argued back and forth ad infinitum.

Photography experts have pointed out that certain shadows are not as

dark or light as they ought to be; the focus in certain areas is not as

sharp or fuzzy as expected; or that the picture could be a

superimposition of two photographs (which was perfectly possible with

the technology of the day).

Some have reasoned that it would have been impossible to take a sharp photograph of a moving object with a bulky plate-camera (even on a tripod) in a wind of between 24 and 27 MPH. Yes; but can those allegations be easily, yet convincingly, proved to the satisfaction of a layman of average intelligence? Perhaps not.

Some have reasoned that it would have been impossible to take a sharp photograph of a moving object with a bulky plate-camera (even on a tripod) in a wind of between 24 and 27 MPH. Yes; but can those allegations be easily, yet convincingly, proved to the satisfaction of a layman of average intelligence? Perhaps not.

Therefore,

the above analysis has been conducted, simply and directly, by

reading-off numbers from a ruler laid on photographic prints. The basis

of the proof is understandable to any child who can crayon a believable

picture of trolley-car wires disappearing into the distance. There is no

latitude for quibble that the sun “might have been shining over there,

but not over here,” to produce the effects which cause the experts

doubt; or that the wind might have suddenly dropped sufficiently to stop

the tripod — standing on sand, remember — from shaking.

Bottom line: It

is impossible for the iconic First Flight picture to have been taken

from a 4-foot tripod on level ground, as has been claimed over the last

century. The rules of perspective (a.k.a. the laws of physics) prove it

could not be so. Period.

Perspective

shows the flight taking off from a hill; named witnesses who, puffing

and panting, carried the airplane up there, also say it flew from a

hill; features in the land show the launch rail and adjacent camera

standing on a hill that is higher than the ground in the middle

distance. Which part of the word “hill” didn’t the Wrights understand?

Below is a simple contour map, showing how all these three

self-reinforcing sources infer the scene should be interpreted.

To

encompass the extra land area visible behind Wilbur in the 1903 picture

would require a vantage point significantly higher than 4 feet 3 inches

above mean ground level. But there is no way that John Daniels

manufactured a giant tripod to create a false position for the horizon,

because the perspective in any image is either all correct, or it is all

wrong. As is now obvious, other things in the First Flight picture are

inconsistent with each other.

Forgive

the tripod-related triple leg-pull, good reader, for it is made with a

serious purpose. The “super-size tripod” is a joke — and so is the claim

that the Flyer “Started from Level”.

How the picture would have looked if taken on level ground with a tripod camera. Note that the horizon (discounting the dunes protruding above it) is lower on Wilbur’s body, and level with the Flyer’s bottom wing.

| |

| In this picture, the horizon is shown level in relation to the picture plane, demonstrating that in the published original (below) the camera was tilted to the left. |

|

The original picture again for quick comparisons to the adjustments shown above.Note again where the horizon is in relation to Wilbur's head |

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Note: "Kitty Hawk: A New Perspective" is a contribution to our blog by one of our most valued editors. He is an expert on aviation history. Comments are always welcome.