"Only a fool of a scientist would dismiss the evidence and reports"What we need is not the will to believe but the will to find out." - Bertrand Russell

in front of him and substitute his own beliefs in their place."

- Paul Kurtz

| |

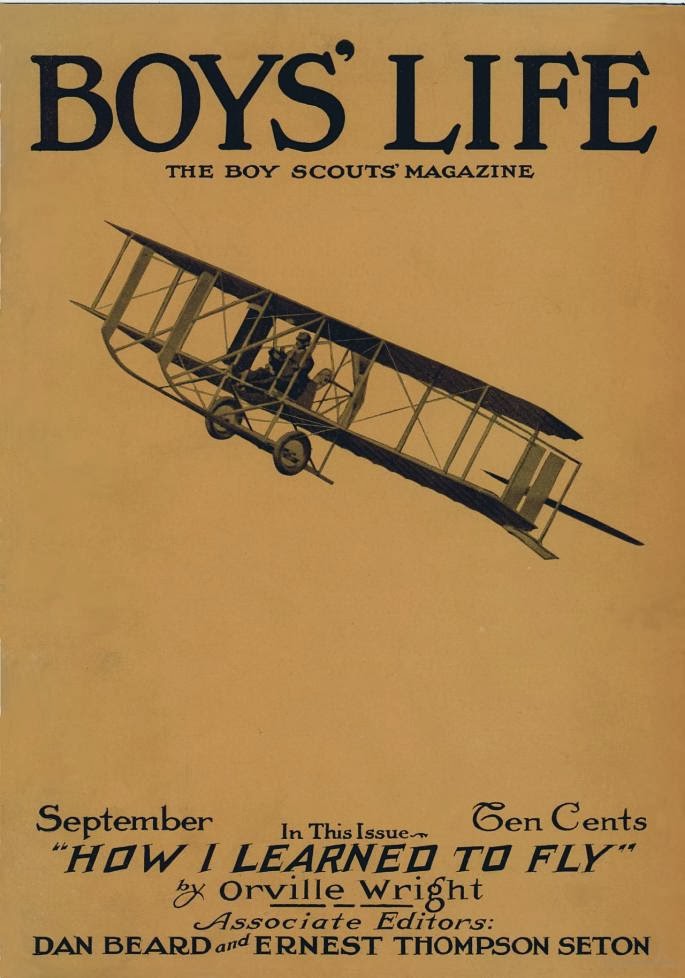

| The cover of Boys' Life magazine Sept., 1914 |

This,

of course, implies that the only statements we can rely on, according

to these historians, are the statements of the Wrights, themselves. But what if the Wrights contradict themselves? Then even the historians have a dilemma.

Fast

forward to the year 1914. It's important to note that Wilbur has died

in 1912 of typhoid. Orville has gone into debt to buy back the stock of the Wright

company. He plans to sell to another group of investors in Dayton. The disgruntled

stockholders of the original company are glad to sell, because they have

found that Orville is unable, or refuses, to attend to business, and

the Wright Company has been run into the ground. This despite the fact

that in January, 1914, the company has paid for and won the final

judgement against Glenn Curtiss in his last appeal against the Wright

lawsuits. Now Orville needs to collect money from all of his patent

infringers. Which, apparently, according to the judges, includes every single

aviator who dares to fly and make any money in the business.

But Orville wants out of the aviation business. What does he want? One clue is in an interview Orville gives to Boys' Life, the magazine of the Boy Scouts of America. Among other glaring inconsistencies with the Wright brothers' previous

narrations of their first "flights" is Orville's new story. He tells the Boy Scouts that he was the one who made the last and longest claimed flight on December 17. Orville has the byline. So we have to

assume from his past history that Orville either "approves" of the story, or somehow doesn't know

about the many discrepancies in it. This is difficult to believe and he

has ample opportunity to correct it. To easily read the full story, please click the link to Boys' Life.

|

| Boys' Life Magazine, 1914, which includes Orville's story of the "first flight" |

In a previous entry, we established that the Wrights official

statement about the claimed flights December 17, 1903, was as follows

1. Orville-- estimated 120 feet (100 feet beyond the track)--12 seconds

2. Wilbur--estimated 175 feet--13 seconds

3. Orville--estimated 200 feet--15 seconds

4. Wilbur --measured 852 feet--59 seconds

According to their joint story, Wilbur won a coin toss and made the first attempt on December 14, but he failed to fly and broke some parts of the plane. Then after repairs, it was Orville's turn to go first on the 17th. So, second that day was Wilbur's turn, third was Orville's, and the fourth and last was Wilbur's. It's important to note that when he was alive, it was Wilbur who was given credit for the only flight that is considered long enough by some, including Tom Crouch, to be considered "sustained," the flight of 852 feet. But then, of course, to be a flight, it would have had to be made from level ground like the Wrights said, not from a hill, assisted by gravity--as witnesses Daniels and Etheridge stated.

|

| Boys' Life Magazine, page 2 |

|

| Boy's Life Magazine, page 3 |

|

| Boys' Life, page 4, where Orville claims the longest flight of 1903 from his own brother |

The circled section on the last page, page 4, of the Boys' Life article (above) by Orville Wright is transcribed below. Note, as stated, that Orville gives himself credit for the last and longest flight (57-59 seconds) that has been credited to Wilbur before. But Wilbur has died and can't correct his brother.

I couldn't turn, of course--the hills wouldn't permit that--but I had no great difficult in handling it. When I came down I was eager to have another turn....""The usual visitors did not come to watch us that day. Nobody imagined we would attempt a flight in such weather, for it was not only blowing hard, but it was also very cold. But just that fact coupled with the knowledge that winter and its gales would be on top of us almost any time now made us decide not to postpone the attempt any longer.My brother climbed into the machine. The motor was started. With a short dash down the runway the machine lifted into the air and was flying. It was only a flight of twelve seconds, and it was an uncertain wavy, creeping sort of a flight at best, but it was a real flight at last and not a glide.

Then it was my turn. I had learned a little from watching my brother, but I found the machine pointing upward and downward in jerky undulations. This erratic course was due in part to my utter lack of experience in controlling a flying machine and in part to a new system of controls we had adopted, whereby a slight touch accomplished what a hard jerk or tug made necessary in the past. Naturally, I overdid everything but I flew for about the same time my brother had.He tried it again the minute the men had carried it back to the runway, and added perhaps three or four seconds to the records we had just made. Then after a few secondary adjustments, I took my seat for the second time. By now I had learned something about the controls, and about how a machine acted during a sustained flight, and I managed to keep in the air for fifty-seven seconds.

Now compare this account with the account in Orville's diary as follows:

" Thursday, Dec. 17 - When we got up a wind of between 20 and 25 miles was blowing from the north. We got the machine out early and put out signal for the men at the station. Before we were quite ready John T. Daniels, W.S. Dough, A. D. Esteridge, W.C. Brinkley of Manteo and Johnny Moore of Nag's Head arrived. After running the engine and propellors a few minutes to get them in working order, I got on the machine at 10:35 for the first trial. The wind, according to our anemometers at this time, was blowing a little over 20 miles (corrected) 27 miles according to the Government anemometer at Kitty Hawk. On slipping the rope the machine started off increasing in speed to probably 7 or 8 miles. The machine lifted from the truck just as it was entering on the fourth rail. Mr. Daniels took a picture just as it left the tracks. I found the control of the front rudder quite difficult on account of its being balanced too near the center and thus had a tendency to turn itself when stated so that the rudder was turned too far on one side and then too far on the other. As a result the machine would rise suddenly to about 10 ft. and then as suddenly, on turning the rudder, dart for the ground. A sudden dart when out about 100 feet from the end of the tracks ended the flight. Time about 12 seconds (not know exactly as watch was not promptly stopped). The lever for throwing off the engine was broken, and the skid under the rudder cracked. After repairs, at 20 min. after 11 o'clock Will made the second trial. The course was about like mine, up and down but a little longer over the ground though about the same time. Dist. not measured but about 175 ft. Wind speed not quite so strong. With the aid of the station men present, we picked the machine up and carried it back to the starting ways. At about 20 minutes till 12 o'clock I made the third trial. When out about the same distance as Will's, I met with a strong gust from the left which raised the left wing and sidled the machine off to the right in a lively manner. I immediately turned the rudder to bring the machine down and then worked the end control. Much to our surprise, on reaching the ground the left wing struck first, showing the lateral control of this machine much more effective than on any of our former ones. At the time of its sidling it raised 12 to 14 feet. At just 12 o'clock Will started on the fourth and last trip. The machine started off with its ups and downs as as it had before, but by the time he had gone over three or four hundred feet he had it under much better control, and was traveling on a fairly even course it proceeded in this manner till it reached a small hummock out about 800 feet from the starting ways, when it began its pitching again and suddenly darted into the ground. The front rudder frame was badly broken up, but the main frame scuffed none at all. The distance over the ground was 852 feet in 59 seconds."

| Pages of Orville Wright's diary in which he details another version of the December 17, 1903 flights |

Again, given that Orville Wright was a watchdog when it came to getting publications "right," it's a fair bet that he was aware of the multiple contradictions in the "Boys' Life" magazine to earlier statements both brothers made. But can we prove Orville knew about the "errors"? See the next post

. To be continued.